- You are here:

- Home »

- Blog »

- Exploring Your Internal Map Of Reality (Series) »

- Exploring Your Internal Map Of Reality Part 5b: Values (Part 2 of 2)

Exploring Your Internal Map Of Reality Part 5b: Values (Part 2 of 2)

Continued from Part 1

Motivation is triggered by a number of factors

Now here’s a short exercise that you can run in your mind to make the connection between values and motivation.

Now here’s a short exercise that you can run in your mind to make the connection between values and motivation.

Think of a time when you were totally motivated. It can be anything such as getting a cup of coffee or asking someone out on a date.

So in your mind go back to that time, step into your body and run through what happened. Do you see what happened, or did you hear or smell something? Or was it one of the other senses?

Is it something that was or is important to you?

If you saw it, how big was the picture, how bright was it? Was it focused or unfocused? Was it color or black and white?

If you heard it, how loud was it? Was it a low sound like a rumble, or was it a high sound like a bird call?

So if you saw it, play around with your image:

Try and make it really small… does it seem more or less important? If you de-focus it, does it become more or less important?

Do the same if you heard it or smelled it – make the sound louder or softer, or the smell stronger or weaker. Does it get more or less important? Does it still motivate you?

So the point of this exercise was to illustrate that your values are a prime source of motivation, and that the way that external stimuli are presented also have a bearing on how important these values are.

Towards and Away Values

When people start to elicit their values, they discover both what they want and what they don’t want. For instance, ‘poverty’ can be seen to be an ‘away’ value because it is something that most people don’t want. Conversely people have a ‘towards’ value such as security. However some ‘towards’ values can actually be ‘away’ values.

The value Security I mentioned above can be formed as a result of being insecure and desiring the opposite, or moving away from insecurity.

It’s important to be aware of this because people often focus on the ‘away’ and end up getting the opposite of what they want!

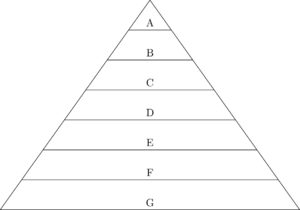

The Values Hierarchy

Another point to know about values is that they are organized as part of a hierarchy. In other words, one value can be higher on the list than another.

Another point to know about values is that they are organized as part of a hierarchy. In other words, one value can be higher on the list than another.

There are various ways of determining our hierarchy of values. One approach is to simply sort them high to low.

For instance you can write down a list of 10 things that are important to you and then sort them – for instance, take ‘Freedom’ and ‘Family’ and ask yourself which is more important. Then take Freedom and another value such as ‘Harmony’ and compare them.

Then take Harmony and Family and compare them. In this process, one value will then stand out as the most important of all three, followed by the next most important and finally the third.

This method is very thorough, but also very complex and time consuming when you have more than 3 values to sort. It is the algorithm used by all computers to sort data, but requires a computer to do it quickly!

However our subconscious mind can and does do it automatically, it’s just that our conscious mind can only deal with about 4% of what the subconscious mind can.

Another method takes the approach of what motivates or inspires us more.

It asks you to supply 3 answers to each of the following questions:

- What do you love to talk about?

- What do you love to research?

- What abilities do you love improving?

- What do you love to contemplate?

- What do you know a lot about?

Once you’ve done that, for each of the 5 questions above, ask the question:

‘Which of the three answers inspires you the most?’

and then

“What feelings do you get from this?”

This will find your top three values without the tedium of the sorting routine above.

Values Conflicts

In addition to explaining why somethings are more important to us, the hierarchy of values it also explains things such as ‘values conflicts.’

In addition to explaining why somethings are more important to us, the hierarchy of values it also explains things such as ‘values conflicts.’

A values conflict occurs when two values have a similar rank in the hierarchy, but which seem to be incompatible with each other. For instance, ‘freedom’ might be one value and ‘family’ might be another.

Freedom on its own is fine, but if you have a family that has equal importance, there will be times when these two values will clash. Most people can handle this by negotiation – for instance allowing Daddy some freedom time to go to the pub with his mates, or making a special time each week for all the family to be together.

However sometimes the process breaks down and some work is required to resolve the conflict.

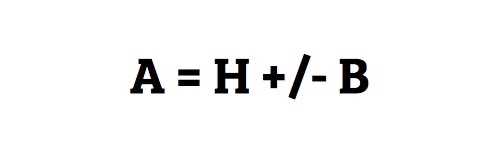

This is done by using a ‘linking formula’:

The way it is phrased is “How will A (new value) Help me/us get more/less of B (new value).”

For instance:

“How will growing my business help me to spend more time with my family?” or

“How will investing in education help me improve my relationship with my partner?”

If you can supply at least one reason (but the more the merrier), you are well on your way to resolving the conflict.

In Summary

Knowing your values and their relative importance to each other is a key way to understand how you process the world both outside and inside you.

Knowing your top values gives you more certainty in your behavior, and knowing how to fix value conflicts results in more desired mental states such as happiness and peace of mind.

A key way to know your values is to do the exercises above, but even more valuable is to become aware of how you create them in the first place and how you act upon them.

This can be done through various practices such as mindfulness and meditation. If you would like to try a free sample of the ‘Holosync®’ meditation program, visit this website.